5 High-Impact Strategies for Reading Intervention

Currently, in the literacy space, there’s a lot of talk about whether using high quality curriculum is enough to help teachers provide effective evidence-based literacy instruction and what role teacher knowledge and autonomy have to play. In my experience as an educator, it is essential that teachers have access to high-quality materials but districts need to be cautious when rolling out new programs or curriculum. It isn’t enough to just give teachers access to high quality materials. Literacy educators need an understanding of how all the curricular materials fit together to form a framework that supports the strands of Scarborough’s Reading Rope.

What I have appreciated most this year is that although my district purchased an intervention program, I am not entirely reliant on those lessons. I lean on the knowledge I have gained from the learning I have engaged in around implementing evidence-based practices. It is through my teacher-knowledge that I can now recognize when a curriculum may fall short in some areas such as the amount of cumulative review provided or how much encoding practice we engage in on a daily basis.

Teachers need to know that while high quality materials are a starting point, there is always room to add necessary support into lessons. Some might refer to this as the intersection of curriculum and teacher knowledge. One is not more important than the other, but instead they support one another in advancing classroom instruction.

Below I will outline 5 evidence-based practices that I consistently utilize and layer into the curricular lessons I have been tasked with implementing this school year. One of the most challenging tasks posed to teachers is how to translate research and knowledge into classroom instruction. Specifically, what does evidence-based instruction look like, and how does it fit with what I am required to teach? Oftentimes after attending a professional development session I like to immediately try out a practice in my intervention space. If I find it to be effective with the students in front of me, I will try and find more ways to incorporate that practice. Here are 5 of the most effective strategies I’ve had a chance to embed in my curriculum and implement with intervention students this school year.

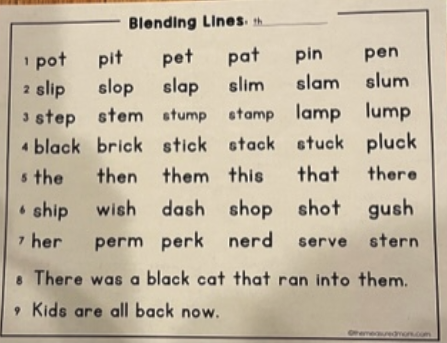

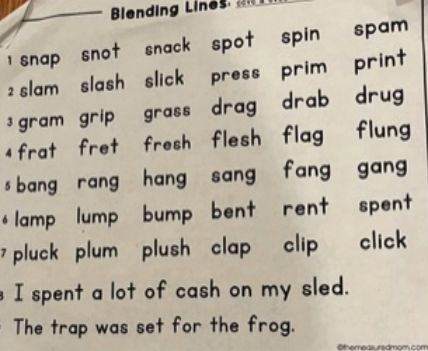

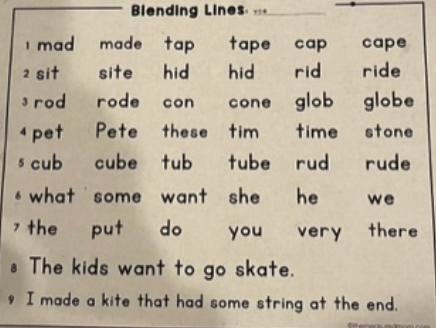

Blending Lines: Blending Lines is an extremely versatile practice that I borrowed from Wiley Blevins’s book, A Fresh Look at Phonics. Blending lines consists of 9 lines. Each line presents words that are specific to decoding a phonics skill or pattern. Many of the lines use minimal pairs so students really need to attend to the subtle differences within words such as pot and pat, where the medial vowel changes. The lines move from simple to more complex skills and lines 8 and 9 include sentences for practice with connected text that can even be pulled from a decodable text being used.

I typically use blending lines for review at the start of each lesson for about 2-4 minutes. Students, after reading these lines, can walk away with this resource to practice on their own in class or even at home. I find this practice to be effective in reviewing past skills, repetition of a new skill being introduced, as well as having the ability to incorporate tricky words in the connected text lines all in a short amount of time. This is extremely important in an intervention setting because many students need increased repetitions before skills are learned to mastery, something which I have found the current curriculum to be lacking.

A second strategy I utilize quite often is Wiley Blevins’ Read-Spell-Write-Extend routine. Currently in the intervention lessons I use, we introduce students to irregular words. I draw students’ attention to the regular and irregular phonemes and the corresponding graphemes used to spell these words, but there is not enough encoding practice for these words. I find by including this read-spell-write-extend routine students get more practice with orthographically mapping these words and more repetitions. This added practice allows students to both decode, encode, and see these words in the context of connected text.

This next practice supports increasing tier 2 vocabulary usage. The students I often encounter in interventions are still learning to crack the alphabetic code. Therefore, they are learning phonics patterns and need to read decodable text in order to practice reading specific patterns. After attending a conference where Wiley Blevins presented, I began layering a tier 2 vocabulary word onto the decodable text we were reading. For example, if we were reading about a specific animal like a snake or frog, I might introduce the word “shelter.” This would not be a word in the text, but rather a solid tier 2 word that correlates to the text. We would explore this word and circle back to it after reading. I might ask the students where snakes find shelter? Students could also potentially use this new word in their writing about reading. This is a simple way to introduce related tier 2 words into the reading of a decodable text and expand vocabulary. This strategy also offers an easy way to maximize the impact of using a decodable text by allowing us to address both strands of Scarborough’s Reading Rope at the same time. This practice also supports oral language development and expands vocabulary growth, which in turn increases the students’ ability to comprehend the text in a deeper and more meaningful way.

After watching Dr. Matthew Burns on various webinars and hearing him speak on several podcasts, I started using paragraph shrinking as a tried and true method for increasing comprehension. Lindsey Kemeny, another well-respected practitioner, has also utilized this strategy in instruction and has outlined it in her book, The 7 Mighty Moves. After students read a paragraph of a text they look for the main who or what of the paragraph. Then, they look for what was the main thing that happened to the who or what. Students practice shrinking down this main idea to 10 words or less. This strategy has been invaluable in helping students identify the important parts of each paragraph as well as how vocabulary and syntax of a sentence can influence the length of a sentence. For example, instead of listing every single detail students can group ideas under one term such as living things or materials. It forces them to be succinct and to get to the main point.

One additional strategy that has a huge payoff is the because, but, so sentence expansion activity from Judith Hochman and Nataline Wexler’s book, The Writing Revolution. This strategy can be used in any content area as well. Students take a given kernel sentence like, “Boats are important,” and add because, but, and so to expand their sentence. This strategy forces them to think about expressing the information they learned from the text in three entirely different ways. These last two practices are ones I can utilize with students reading decodable text as well as students reading grade-level text.

Each of the five strategies I’ve shared are consistent practices that I weave into the intervention lessons that I am required to teach. I have found that these practices are effective for my students in areas that the curriculum is lacking. While the high quality curricular materials I have been given provide me with a framework, it is essential that I know when my students might need more. All of these practices are high utility and do not require a ton of extra time to implement. Without these added pieces my instruction would be missing elements that are essential in order for students to make progress. This kind of layered instruction is where I see the intersection between teacher knowledge and high quality curriculum having the greatest impact. It is not one or the other, but rather a balance of both.