The Middle School Literacy Bottleneck

How often do we, educators of older students in middle and high school, find ourselves working with students who struggle with reading, writing, and spelling?

Many of these students seem to wind up in classrooms with well-meaning adults who, as middle or high school teachers, don’t consider that they will have to teach literacy skills that were supposed to have been addressed years earlier. Teachers who work with these students often note how these students will do anything to avoid class and how their behaviors are a constant distraction. This is not sustainable– for the long-term health of a school community or more importantly for the individual students who are suffering. I call this phenomenon the literacy bottleneck.

As a reading interventionist at a middle school, my job is to try to help older students acquire skills that are missing or obscured by inefficient habits such as guessing at words. My perspective has been shaped by working with students who tend to have more complex profiles. I’ve had to adapt and learn and grow because, as one of my mentors pointed out to me, the most challenging students are our best teachers.

In examining the literacy bottleneck in middle school, I can’t promise I have all or any of the answers. There are more experienced practitioners in the field who have been tackling these issues for a much longer time than I have. But speaking from my own experience, I think there are things that middle school and high school teachers and schools can do now without having to wait for big paradigm shifts that may never come.

Coursework

Aside from ensuring that early intervention and evidence-based literacy practices are in place at a young age, I believe that every teacher should complete coursework in reading and writing instruction regardless of the subject area. They should understand the language and how to teach it. It’s a guarantee you will get older students missing foundational skills who feel angry and hurt because they are spending hours each day in a setting where they are expected to use skills they don’t have yet. You want to be able to help those students and equip them with the skills they need and desperately want.

I also believe every teacher should complete coursework and ongoing professional development related to instruction for students with learning disabilities. It’s another guarantee every teacher will have a number of students in their class who will require specialized instruction for a disability. While a classroom teacher doesn’t necessarily need to be that specialist, they should at least understand how these children learn best. The things that ultimately benefit students with disabilities benefit everyone––some children just require more. Having access to evidence-based literacy instruction and weaving opportunities for repeated practice of foundational skills into every class will build up the resilience and fortitude of students. Even students who protest and can move through work rapidly benefit from the extra practice. Science shows us that repeated practice of really any skill is how one achieves mastery––from painters to electricians and on to doctors and lawyers––there are skills that require automaticity so the brain is free to grapple with more challenging tasks.

Data

Data is often a word that makes teachers groan. They are required to collect data and maintain the paperwork, but usually the data being collected is not being used to a teacher’s advantage. Sometimes teachers are collecting data that isn’t going to be helpful for the area they need. Work samples, for example, are often considered data, but they are a relatively subjective measure. Work samples can provide useful information, especially looking at patterns of errors or if a student is struggling with something like their letter formation or the science concept being tested. Ultimately the data that will be of most benefit to everyone is something standardized that measures a skill for mastery over time.

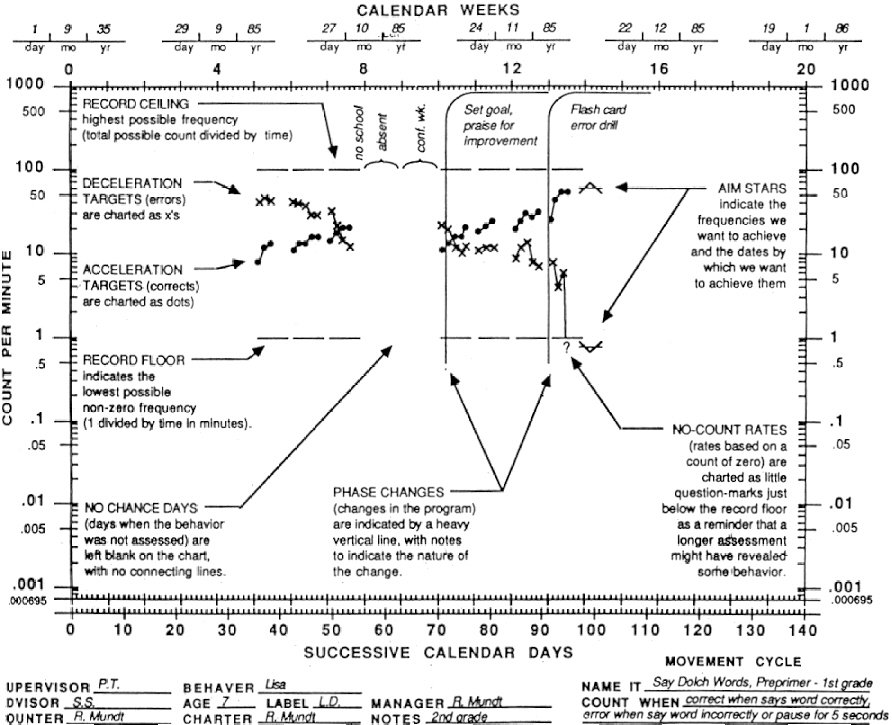

I use standard celeration charts myself with my one-to-one students because I can track each skill, and I can check to see if my intervention is having an effect. Classroom teachers may not have the time to input this level of detail if they have larger classes, so having a system like AIMSWeb or FASTBridge that has calibrated probes in math, reading, and other target areas can provide a solid big picture look at where a student is. As someone who considers himself creative, charts and graphs are not something I ever thought I’d find myself actively seeking out. However, when working with students, I know how important it is to be able to not only have clear, accurate data for myself, but also have something I can show to the student and their family. Seeing progress in the data can be a huge boost for students. Ultimately, if we aren’t charting students and we aren’t monitoring their progress in the skill areas of need we are flying blind. The idea with data driven instruction is to have as clear a picture of each individual as possible.

Screening

Schools need to identify struggling learners quickly and determine who is struggling for neurobiological reasons and who is simply missing skills. The students who do not have a disability don’t require as much instruction; they may just have bad habits or were never taught certain skills. It’s never easy to balance a middle or high school schedule and also teach these students skills they should have acquired years ago, but it is in everyone’s best interest to take the time to do so. Once the skill gaps are filled in, it will be easier to help students acquire background knowledge and move on to more advanced literacy skills like morphology and comprehension of complex texts. Using student data from progress monitoring systems and tools such as standard celeration charts can help guide teacher instruction and divide up often limited resources accordingly. Moreover, trying to get a child who is missing key foundational skills to engage with a task they don’t have the skills to complete on their own is ultimately not going to benefit the instructor or the student. This is another reason it is beneficial for teachers to not think of themselves in a siloed fashion, but rather be open to having to address skill areas they may take for granted.

Resource Distribution

Part of the problem that schools are dealing with right now is that there are so many students struggling with reading, writing, spelling, and basic math. Some of these students have complex learning disabilities. Others do not. In order to prevent the literacy bottleneck, schools need to employ trained, specialized staff to support the students with the most complex disabilities.

However, while some interventions do require specialists like speech pathologists and occupational therapists, there are also many interventions that can be delivered by most any staff member. I have trained college age students in delivering effective reading instruction. The brain may be complex, but many of the most common interventions don’t require complex solutions or complication training.

If schools can identify and understand what each struggling student needs and pair them with an appropriate interventionist, be it a SLP, an OT, a paraprofessional, an after-school tutor, then more students will make more progress and the school can allocate resources more effectively, efficiently, and equitably.

Conclusion

The way our system works makes it very difficult to help some of our students. My saying to go and get training in data collection and in reading instruction is intentionally non-specific because there are several data collection systems and programmatic options that are evidence- based. I happen to use certain programs and certain tools in my practice that I’m always glad to share, but I don’t want to come across as dictatorial. My feeling is when making choices, it’s important to look at the student in front of you and choose the tools based on that individual’s data.

It’s also easy for me to say some of these things because I’m not managing thirty students at once, I’m usually seeing students one-to-one. I think it’s important to really have different options available, as many as possible, that are evidence-based, so that a teacher can make the most informed decision for their group of students and for students who require more individual attention. I think sometimes we can all get a bit attached to the tools we are familiar with––until we reach a student where those tools don’t work, and we have to start from scratch. At the end of the day, it’s about seeing that each child has the skills they need to have choices in life. We can’t perform miracles, but we can make decisions on a macro and a micro level within the system that will benefit the maximum number of students.