Reading Myths: Part 1

This week, I’m sharing four commonly-held myths about reading versus the actual realities. Unfortunately, many people—from teachers to pediatricians to school leaders to professors of education—believe and spread these myths. You might hear them at your child’s annual physical appointment or at parent-teacher conferences or if you happen to have taken an education class in college or graduate school. They’re everywhere.

Interview with Heidi Martin

What advice do you have for teachers who want to learn more about the Science of Reading?

Louisa Moats says, “Programs don’t teach, teachers do.” I recommend teachers start with training because there is no perfect program. I also recommend the book Know Better Do Better if you’re brand new. It’s a practical read that will give a good starting point. Even programs that are SoR aligned are always missing something, and there is absolutely no substitute for acquiring the knowledge for yourself. No one can take that away from you!

So About That Seidenberg Talk…

But here’s the problem. Seidenberg doesn’t address what current teachers should do as we sort out the efficacy, efficiency, and equity of our current programs. No really, what should they do in class tomorrow? Should they dust off their Fountas & Pinnell? Keep doing what they’re doing? If you’re a second grade teacher who is trying to learn about the science of reading and you heard this talk, you’d be understandably confused, likely worried that you were failing your students, definitely questioning your ability and instincts. This confusion doesn’t help anyone, definitely not the second-grade students who are trying to learn how to read.

Science of Reading Classroom

So, last week, I decided to take some of my own advice, and I started a Twitter account: SoR Classroom. The account does one thing. It shares videos, photographs, and work samples to illustrate what the Science of Reading looks like in the classroom…In addition, the posts demonstrate how joyful, vibrant, and interactive these classrooms are. And they showcase the brilliant work that students and teachers are doing in these classrooms. How many 4th graders are equipped to paraphrase the Declaration of Independence? How many kindergartners can use the word “barter?”

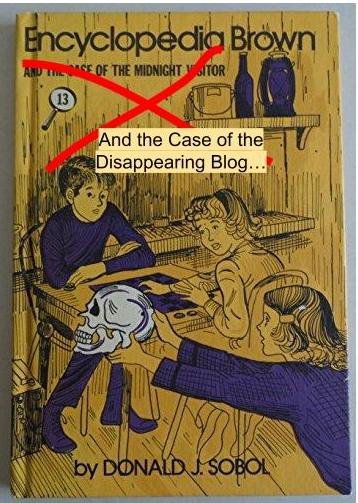

The Case of the Disappearing Blog

But when you try to access the blog today, it’s no longer available on the Psychology Today website. It was removed sometime between February 10th and February 22nd, when I found a cached version, linked here. I’m not in a position to speculate about why the post was removed. I’ve asked Psychology Today for comment but have not heard back. But since I was able to retrieve the post, I ask that you share it widely and loudly! We need outlets outside the education world like Psychology Today to publish work like this if the Science of Reading movement is to grow.

The Next Time You Fire Off Some Tweets…

And that’s because I think there’s a tension between parental advocacy for a particular instructional practice and respecting teachers. When you get down to it, if parents are advocating for change in schools, they are saying “teachers are wrong to do X. they should do Y instead.” Advocacy is inherently critical, and in this case, it is critical of teachers’ knowledge and practice.

What Can SoR Advocates Learn from Balanced Literacy?

So where does that leave SOR? I think it means we need to stop talking about data and statistics so much. Data might activate and convince people who don’t already have strong opinions about reading instruction. But it’s not going to work on the teachers and administrators who already have their own methods and lived experiences. Balanced literacy advocates aren’t running around using data to champion their ideas (This is partially because they don’t have great data to cite). Instead, tell stories about your students and children who benefited from SOR. Watch the Purple Challenge with your coworkers and your parent friends. Talk about Bethlehem or Goose Rock. But drop the data.

Reimagining Psychoeducational Testing: Scarborough’s Reading Rope

Every student with a language-based learning disability should have an annotated and personalized version of the reading rope in their psychoeducational testing.

Every parent of a child with a language-based learning disability should be able to understand their child’s “reading rope.” Every child should understand this too when they’re curious and ready.

Every school needs to be prepared to address the individual deficit strands with high-quality Tier 1 instruction and evidence-based interventions.

Friday Musings: What’s the Matter with Winchester?

As states begin to enforce screening laws and as districts begin to screen students more systematically, they need to assess how effective their tools and methods are. They should be asking themselves: “Why didn’t this particular 5th grader get flagged 5 years ago?” “What warning signs did me we miss?” “What can we do differently next time?” Schools won’t catch every student with dyslexia in first grade and kindergarten, but I’m pretty confident that they should be able to identify more students than they are identifying now.

Relational Organizing and the Science of Reading

This is not easy work. It’s way more comfortable to trade compliments and share ideas amongst ourselves online. But this is important work. We can wait for the movement to grow on its own. Or we can intentionally, systematically convert and mobilize our friends and family members to join us in changing the system. And the cool thing about relational organizing is that once you get your friends and family onboard, you can teach them how to become relational organizers too.

Friday Musings: Aperture

I’ve spent a lot of time this week thinking about two things: 1. Competing theories of change in education and 2. How to grow the science of reading movement. Kim’s theory—that you’re nowhere without the teachers—makes me question: who is leading the movement now, who is perceived to be leading the movement, and who should lead the movement in the future? Where do the teachers, the ones who are going to have to enact the desired change, fit in? What do they need? What do they think? What do they want?

Growing the Science of Reading Movement

The science of the reading movement needs to keep growing. It needs to convert and mobilize schools of education, parents, policymakers, departments of education, school boards, curriculum developers, pediatricians, and most of all teachers and school leaders. No single approach is going to work on everyone. But at the end of the day, the more we talk about the science and the social justice of reading, the more we tell relatable and compelling stories about successes as well as failures, the more we make our materials and arguments accessible and inclusive, the more successful the movement will be. We need to start now. Our children’s futures depend on it.

Friday Musings: Changing The System

The Black and Dyslexic Podcast from Winifred Winston and LeDerick Horne wrapped up its first season this week. What a triumph! The podcast does three things, in particular, exceptionally well. First, the hosts directly confront the reality that IEP and 504 programs are failing Black students and families. They make the causes (racism) and the consequences (limited opportunity and options) of that failure abundantly clear. Second, they invite guests to tell their personal stories, which illuminate the inequities and racism of the system while also building empathy, community, and connection. But they don’t stop there. Third, Winston, Horne, and their guests then offer specific advice, tips, and information to other parents who are trying to make a broken system work for their children. My favorite is this recurring refrain: “Extended time isn’t going to teach your child how to read. It’s accommodation. Your child needs an intervention from the school that addresses the underlying issue.” Ultimately, Winston’s and Horne’s podcast succeeds because they are vulnerable, funny, and honest. They help their guests feel at home, and they make their audience feel like they’re on their team.

Elephants in the Room: Why Does The Science of Reading World Skew Conservative?

The science of reading, evidence-based reading instruction, whatever you want to call it, is not a partisan issue. There is nothing left or right about the facts of how students learn. We know better than ever how to teach all students to read, but we’re not doing it. Instead, we’re politicizing our students' futures.

Friday Musings: Goose Rock Rocks

You need to read this remarkable case study about Goose Rock Elementary. In 2012, 23% of 3rd graders at Goose Rock were reading proficiently. In 2019, 90% were. What happened? Through a partnership with Elgin Children’s Foundation, Goose Rock’s literacy curriculum was overhauled, its teachers were retrained, and new interventions for students reading two-three levels below grade level were introduced. Notably, these gains came even as the number of students eligible for free or reduced lunch rose from 80% to 85%.

Ideas for 2022: One School at a Time

My eventual plan is to select one elementary school in one of these districts, get to know the parents and community it serves, and work with interested parents to ask tough questions about their literacy curriculum, with the goal of ultimately changing the literacy curriculum to a higher quality one. If I support the parents in launching a campaign to change the curricula, then I’ll choose another school and go from there. Hence, the One School at a Time Project.

Learning in 2021

I spent most of 2021 learning. I learned about the false dichotomy between content and skills. I learned about cognitive load theory. I learned about various teacher education programs, the process by which school psychologists recommend accommodations, and Scarborough’s Reading Rope. I learned about different screeners for dyslexia and conflicting theories of student support, and evidence-based tutoring programs. I learned how to build a website. I didn’t really learn how to use social media.

Accommodations under a Microscope (Part 3)

Some combination of accommodation, modification, and intervention is likely appropriate for most students with learning differences. However, when schools rely too heavily on the former two instead of the latter—and indeed it’s convenient to rely on the former—they are depriving students with learning differences of the opportunity to become more independent and grow new skills.

Accommodations under a Microscope (Part 2)

It won’t be possible for every teacher to “interventionalize” every accommodation, of course. But I think if we take these ideas as starting points—both that students need to be taught how to use their accommodations AND that accommodations are probably most impactful when they’re tied to actual learning—we’ll be on a better path.

Accommodations under a Microscope (Part 1)

In this piece, I am going to undermine the value and purpose of academic accommodations, and I’m going to explain how accommodations can undermine academic progress.