Talk to Teachers: Moriah Geller

In my undergraduate program, we learned about the reading wars and the history of reading. We didn’t learn about phonics or whole language in depth - beyond what each of those meant - but we did learn about “the pendulum,” so to speak, which swung back and forth about every decade. We also learned a lot about motivation and engagement, which was valuable but not sufficient for understanding how to teach kids how to read. After graduating, I went into a master’s degree and credential program. There, too, the literacy courses were mostly focused on motivation and engagement, along with comprehension strategies, state standards, and the components of balanced literacy.

Knowledge Building is Social Emotional Learning

My students cry every year when the dog in “Love that Dog” gets hit by a car. They empathize with Brian from “Hatchet” who is dealing with the pain of his parents’ divorce while attempting to survive in the wilderness. They feel genuine sadness for Annie, a character in “Woods Runner” who loses both of her parents in the American Revolution, and they learn life lessons from Greek and Native American myths. This is social-emotional learning.

How to Tweet Productively

So what’s the lesson here? Here are three that I can think of:

It’s possible to recover from an unpleasant moment or exchange on Twitter, especially if you assume good intent and keep your commentary dispassionate.

Twitter can be a productive forum for nuanced conversation.

But we shouldn’t expect all or most conversations to end in consensus. This one certainly did not.

Using Data to Support Struggling Readers

It may only be the third full week of the school year, but targeted reading interventions are up and running. How did we get here so quickly? A Decision Tree. Data. Team Work. WIN.

Talk to Teachers: Francesca Corino

As part of our commitment to celebrating, uplifting, and highlighting teachers and their incredible work, we’re introducing a regular series called Talk to Teachers, where we interview teachers about their experience teaching reading and learning about teaching reading. This conversation is with Francesca Corino, an instructional coach or pedagogical coordinator at an international school in Brazil. Francesca learned about structured literacy while searching for alternatives to and extra supports for Units of Study. The following conversation was lightly edited for clarity and concision.

Introducing: Talk to Teachers

For the rest of the year, we will regularly share interviews with exceptional reading teachers from around the world. We want to hear directly from teachers about their experience teaching reading. We want to hear from them about their practice, about their education, about their evolution, about the questions they have for researchers, about any hang-ups they might have about “the science of reading.”

Fellowship Reflections: Talk to Teachers

But selectivity is not the goal here. We want to celebrate, uplift, and honor teachers who are doing exceptional work. We want to learn from these teachers. We want to help other teachers replicate what they’re doing. That’s the purpose of this fellowship.

Goyen Literacy Fellowship: Update 1

Ultimately, I want to select fellows that are exceptional teachers of reading, that are bringing joyful evidence-based practice into their classrooms. I want to choose fellows that will effectively capture these practices in bite-size digestible tidbits and will be exceptional models for other teachers that are trying to learn how to translate research into practice.

Announcing the Goyen Literacy Fellowship

I am thrilled to announce our newest initiative: the Goyen Literacy Fellowship!

What does this mean?

It means that we will give teachers $2000 to document excellent literacy teaching in their classrooms. If you like our SoR Classroom project and want to get paid to help us create a library of content like this, keep reading…

What does it mean to read at grade level?

And perhaps you, like me, have wondered: what do these statistics actually mean? What does it mean to be a proficient 4th or 8th or 10th grade reader? What will you struggle to understand? What can you read? What can’t you read? What do you do when you encounter a text that is beyond your grade level? What does that challenging encounter look and feel like?

What I've Learned from @SoR Classroom

More ELL content! More AAE content! There’s no doubt that reading depends on spoken language. There’s no doubt that when a child’s home language is different from General American English (GAE), then learning how to read GAE is going to be more complicated. This is true for English language learners. It’s also true for students who use African American English (AAE). We need more examples of how teachers are honoring and working with these linguistic differences. What does sound-phoneme mapping look like in a classroom of GAE speakers? How do you assess fluency? How do incorporate students’ home languages or dialects into your instructional practice?

So About That ALA Presentation: Final Lessons (Part 3)

I’ve spent the last three blog posts documenting many of my concerns with Drs. Erekson’s and Benke’s work. In the interest of time and space and attention span (yours, mine), I wasn’t even able to write about all of them. Concerns aside, though, at the end of the day, this presentation is not persuasive because it does not actually offer a positive vision of effective, inclusive, exciting, rich, and beautiful reading instruction. They don’t actually propose a comprehensive alternative. Yes, both speak favorably about balanced literacy at times, but they don’t go into what that practice entails or what it means for students in the classroom. The final lesson I hope to leave you here with is don’t just use your voice to criticize what isn’t working and complain about your school’s failure to teach reading effectively. Use your voice to describe and promote a positive, clear, engaging vision of what excellent reading instruction looks like. That is what needs to do as a movement. That is what I will try to do with my voice.

So About That ALA Presentation: Low Expectations and Learning Styles (Part 2)

No one denies that reading progress is strongly correlated with family income and wealth as well as parental education level. What jumps out to me here is that Dr. Erekson is content to blame home and social factors for low reading achievement; he has no interest in interrogating how we can improve in-school instruction to achieve better results for our most marginalized students. To quote Kareem Weaver, “the soft bigotry of low expectations sustains the belief that kids can't learn to read because of poverty and trauma.”

So About that ALA Presentation…(part 1)

If you’ve spent any time on Science of Reading Twitter or Facebook this week, you’ve probably noticed posts about the now-infamous ALA presentation on Science of Reading and libraries. I obtained the recording and slides from the presentation, and unfortunately, it is much worse than the online summary suggests. The presenters don’t just mischaracterize the science of reading as a phonics-only curriculum—the science of reading is neither a curriculum nor does it exclusively or especially focus on phonics. They also conspiratorially imply that a well-funded cadre of parents of dyslexic students, the International Dyslexia Association, Emily Hanford, the Reading League, and various SoR-related companies are pushing the science of reading for profit. Along the way, they misrepresent various reading models, suggest that dyslexia may not be real, and question why we’re changing core instruction just because of a small number of struggling readers.

What I Learned in Physical Therapy

Preparing Teaching: Teacher education should look more like Natalie’s physical therapy education. It’s that simple. That’s the insight. Teachers should receive more education about learning science, cognitive psychology, and the content of their subject area. Then, they should apply that knowledge in an apprentice setting, where they can observe an expert teacher, gradually assume more responsibility, receive frequent and immediate feedback, and debrief their work. This may happen in some teacher development programs. It doesn’t happen in many. It needs to happen in all.

Reading Myths: Part 1

This week, I’m sharing four commonly-held myths about reading versus the actual realities. Unfortunately, many people—from teachers to pediatricians to school leaders to professors of education—believe and spread these myths. You might hear them at your child’s annual physical appointment or at parent-teacher conferences or if you happen to have taken an education class in college or graduate school. They’re everywhere.

Interview with Heidi Martin

What advice do you have for teachers who want to learn more about the Science of Reading?

Louisa Moats says, “Programs don’t teach, teachers do.” I recommend teachers start with training because there is no perfect program. I also recommend the book Know Better Do Better if you’re brand new. It’s a practical read that will give a good starting point. Even programs that are SoR aligned are always missing something, and there is absolutely no substitute for acquiring the knowledge for yourself. No one can take that away from you!

So About That Seidenberg Talk…

But here’s the problem. Seidenberg doesn’t address what current teachers should do as we sort out the efficacy, efficiency, and equity of our current programs. No really, what should they do in class tomorrow? Should they dust off their Fountas & Pinnell? Keep doing what they’re doing? If you’re a second grade teacher who is trying to learn about the science of reading and you heard this talk, you’d be understandably confused, likely worried that you were failing your students, definitely questioning your ability and instincts. This confusion doesn’t help anyone, definitely not the second-grade students who are trying to learn how to read.

Science of Reading Classroom

So, last week, I decided to take some of my own advice, and I started a Twitter account: SoR Classroom. The account does one thing. It shares videos, photographs, and work samples to illustrate what the Science of Reading looks like in the classroom…In addition, the posts demonstrate how joyful, vibrant, and interactive these classrooms are. And they showcase the brilliant work that students and teachers are doing in these classrooms. How many 4th graders are equipped to paraphrase the Declaration of Independence? How many kindergartners can use the word “barter?”

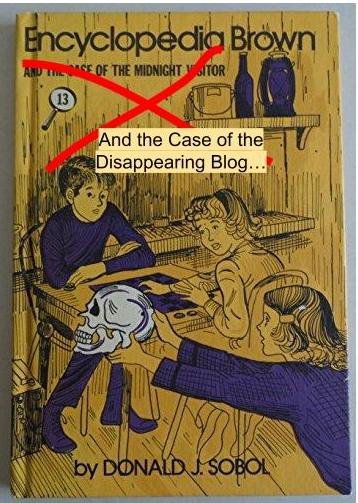

The Case of the Disappearing Blog

But when you try to access the blog today, it’s no longer available on the Psychology Today website. It was removed sometime between February 10th and February 22nd, when I found a cached version, linked here. I’m not in a position to speculate about why the post was removed. I’ve asked Psychology Today for comment but have not heard back. But since I was able to retrieve the post, I ask that you share it widely and loudly! We need outlets outside the education world like Psychology Today to publish work like this if the Science of Reading movement is to grow.